DANGEROUS ORGAN TRANSPLANTS:

Notwithstanding the unfulfilled quest for immortality, man’s endeavor to outdo organ failure and prolong life has been a journey bejeweled with hues of ingenuity. This exciting odyssey has been marked with chimerical events and miracles in the olden times, and, in the more recent, by triumphs of technical and cognitive advances in organ preservation, surgical skill, immunology, management of infectious diseases, and multidisciplinary innovative approaches, which have collated to fructify the realm of tissue and organ transplantation. The remarkable evolution-colored with serendipitous discoveries, tragic accidents, abandoned paths, and incidents that have produced ethical and legal predicaments-stems from a confluence of cultural, legal, and political acceptance of the need to facilitate organ donation, procurement, and allocation. This serial narrative, punctuated with historic pictures, captures some of the major milestones in the saga of transplant medicine.

2500-3000 BC

The Wondrous Xenotransplant

The idea of replacing diseased or damaged body parts has been around for millennia. Mythological, religious, historical, and archaeological texts are filled with fascinating narratives also of organ transplantation. The head and neck xenotransplant on Hindu god Ganesha, born of Parvati, Lord Shiva’s consort, is a classic instance. Although Ganesha’s elephant-head may purely be mythical, or hide a deeper meaning, still it makes for a most ingenious concept, considering the period when Shiva Purana was inked. Puranic Hindu texts, dating back to 2500-3000 BC, also provide a vivid description of reconstruction of mutilated noses using skin homografts.

The ancient Greek mythology is also packed with tales of gods, heroes, and heraldic beasts with chimerical anatomy and abilities. Evidence for autotransplantation of nonvisceral tissues, such as bone, teeth, and skin, have been described as far back as the prehistoric Bronze Age.

1st century AD

Era of Myths and Miracles

The New Testament of the Bible portrays several instances of homologous transplantation. The account of Jesus of Nazareth restoring a servant’s ear severed by Simon Peter’s sword in a battle; of Saint Peter reimplanting the breasts of tortured and mutilated Saint Agatha; and of Saint Mark reimplanting a battle-amputated hand of a soldier are all too well known.

348 AD

Transplant of a Leg

In Leggenda Aura (Golden Legend of Lives of the Saints, 348 AD), the author Jacques de Voragine vividly recounts the “Miracle of the Black Leg.” The accompanying painting portrays the miracle. A Roman deacon Justinian had a gangrenous leg and was in considerable pain. Yet, one morning, he woke up without pain and found himself transplanted with a new leg. This leg was taken from a recently deceased Ethiopian man.

1905

Eduard Zirm, an Austrian ophthalmologist, performed the world’s first corneal transplant, restoring the sight of a man who had been blinded in an accident.

1912

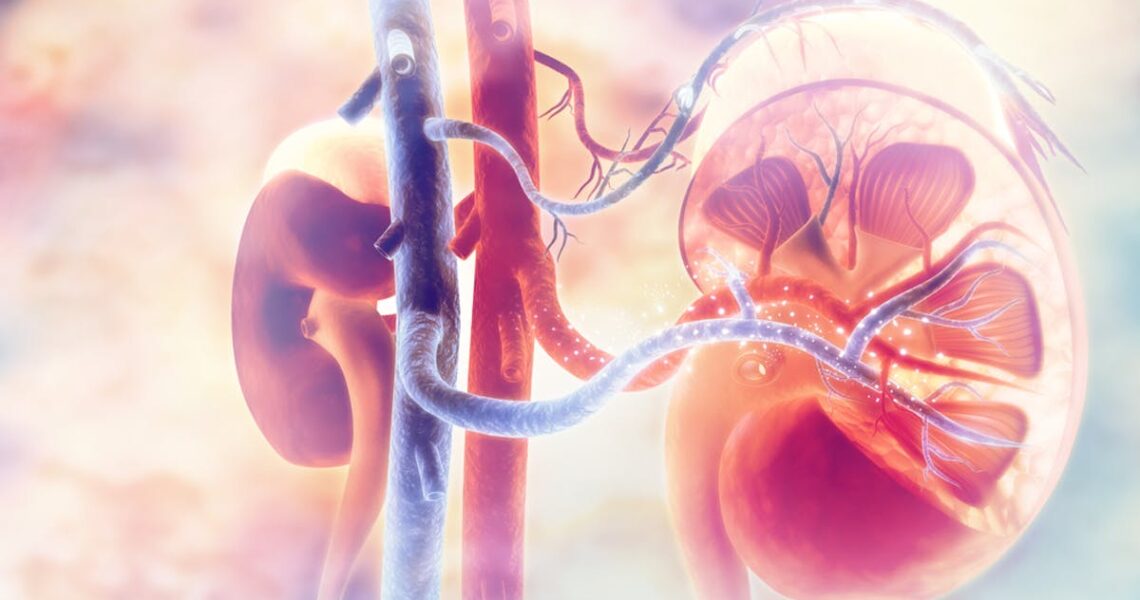

Transplant pioneer Alexis Carrell received the Nobel Prize for his work in the field. The French surgeon had developed methods for connecting blood vessels and conducted successful kidney transplants on dogs. He later worked with aviator Charles Lindbergh to invent a device for keeping organs viable outside the body, a precursor to the artificial heart.

1936

Ukrainian doctor Yurii Voronoy transplanted the first human kidney, using an organ from a deceased donor. The recipient died shortly thereafter as a result of rejection.

1954

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a team of doctors at Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital carried out a series of human kidney grafts, some of which functioned for days or even months. In 1954 the surgeons transplanted a kidney from 23-year-old Ronald Herrick into his twin brother Richard; since donor and recipient were genetically identical, the procedure succeeded.

1960

British immunologist Peter Medawar, who had studied immunosuppression’s role in transplant failures, received the Nobel Prize for his discovery of acquired immune tolerance. Soon after, anti-rejection drugs enabled patients to receive organs from non-identical donors.

1960s

The first successful lung, pancreas and also liver transplants took place. In 1967, the world marveled when South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard replaced the diseased heart of dentist Louis Washkansky with that of a young accident victim. Although immunosuppressive drugs prevented rejection, Washkansky died of pneumonia 18 days later.

1984

As transplants became less risky and more prevalent, the U.S. Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act also to monitor ethical issues and address the country’s organ shortage. The law established a centralized registry for organ matching and placement while outlawing the sale of human organs. More than 100,000 people are currently on the national waiting list.